By Karina Virahsawmy, Assistant Curator, Alfred Gillett Trust

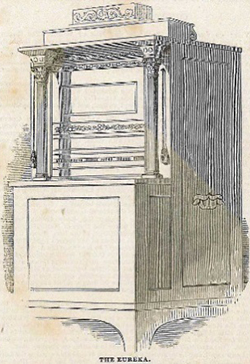

The Latin Verse Machine, named Eureka by its inventor, John Clark, is a curious blend of science an art – a technological creation designed to compose poetry in Latin. It epitomises the Victorian vogue for inventing solutions to push the boundaries of imagination and is a rare survivor of its age.

The Latin Verse Machine, named Eureka by its inventor, John Clark, is a curious blend of science an art – a technological creation designed to compose poetry in Latin. It epitomises the Victorian vogue for inventing solutions to push the boundaries of imagination and is a rare survivor of its age.

Eureka, described as simply as one can, is a mechanical device that uses a system of levers, pulleys and cogs to produces a line of Latin ‘hexameter’, or line of verse numbering six words. It was built between 1830-1845 by John Clark, a member of the prominent Quaker family who founded Clarks the shoemakers.

Why it was made is simple to answer; why not?

During the 18th and 19th centuries, automaton and arithmetical-substitution devices were becoming increasingly popular; Professor Faber’s ‘Euphonia’ was a speaking machine and Babbage’s ‘Analytical Machine’ was the first mechanical computer. John Clark, the Eureka’s inventor, did not make it for its commercial gain but purely for academic interest. I find the most joy in the fact that ‘Eureka’ has no real reason for being, apart from the fact that John Clark was interested in it as an idea. It does not provide answers or remedies, only entertainment and curiosity.

John Clark described it as; “The Hexameter Automaton bears some affinity to an animated being. It possesses a material and an immaterial part, a corporeal and an incorporeal power. Yet it is a thing far inferior to an animal, inasmuch that it possesses no volition or intention, nor any consciousness of its own existence. The materials of which its composed…are subject to delay. It is further subject to injuries and the casual derangement of its parts.”

In July 1845, Eureka was taken to London to be exhibited in the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly as one of its ‘sights of the season’. This was a noted space for exhibiting curiosities and was built in 1812 as a museum for natural science. Previous exhibitions held at the Egyptian Hall included, a ‘living male child with four hands, arms, legs, feet and two bodies’ (1837) and the exhibition of Tom Thumb (1844), with Professor Faber’s Euphonia (1846) exhibited the year after Eureka.

The admission price was one shilling, and such was its success that Clark was able to retire on the proceeds quite comfortably after the exhibition. Positive reviews appeared in Punch and The Illustrated London News as a result of the exhibition and its appearance in London was feted as ‘the machine’s hour of glory’.

The admission price was one shilling, and such was its success that Clark was able to retire on the proceeds quite comfortably after the exhibition. Positive reviews appeared in Punch and The Illustrated London News as a result of the exhibition and its appearance in London was feted as ‘the machine’s hour of glory’.

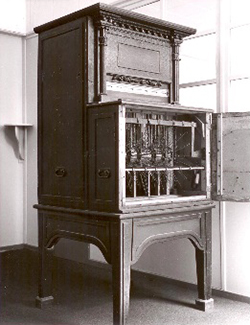

After its exhibition in London, there is a possibility that the machine was exhibited in Bristol, however the search to find where and when, has so far proved fruitless. Eureka was exhibited in the Street Club and Institute, Crispin Hall, before being displayed in C & J Clark Ltd’s. headquarters, both in Street, Somerset. There have been a few attempts to restore, renovate and conserve the Latin Verse Machine through the years, but this partnership project with University of Exeter is the most comprehensive conservation project undertaken to date.

The machine was an evolving entity and underwent various transformations during its lifetime as new mechanisms and features were added or taken away. The Illustrated London News reported that it once played music, with ‘God save the Queen’ accompanying the winding mechanism and an Irish Air signalling that a verse had been produced. A music roll can be seen inside the machine, but the mechanism needed to produce the sound is no longer present, leaving us to speculate how John created this captivating effect. The article also notes that a kaleidoscope was placed on the top of the machine which projected images, but sadly this no longer survives.

A quote from John Clark’s great-niece explained an anomaly that came to light during the internal cleaning and conservation of Eureka. She wrote, “He was the eccentric and clever John Clark, Father’s uncle, and Father used to take us to call upon him at his house in Eastover…He would show us the Latin Verse-making machine which he had invented, and let me put in a penny and see the couplet coming out…”. It was long believed that this was a story told to amuse the children, but during renovation work a coin slot and receptacle for coins was found. Investigation into the mechanism made it clear that the coins still did not initiate the machine and merely collected within it, but this small addition to the machine could have easily been overlooked without this in-depth analysis.

A quote from John Clark’s great-niece explained an anomaly that came to light during the internal cleaning and conservation of Eureka. She wrote, “He was the eccentric and clever John Clark, Father’s uncle, and Father used to take us to call upon him at his house in Eastover…He would show us the Latin Verse-making machine which he had invented, and let me put in a penny and see the couplet coming out…”. It was long believed that this was a story told to amuse the children, but during renovation work a coin slot and receptacle for coins was found. Investigation into the mechanism made it clear that the coins still did not initiate the machine and merely collected within it, but this small addition to the machine could have easily been overlooked without this in-depth analysis.

During the project it was found that the machine originally had a gilded front causing much speculation about its original finish. Whilst the conservation work has not provided all the answers, we have been able to use the findings to date later additions to the machine. Some of the decorative wooden spheres at the front were found to be replacements and were only ever painted black, indicating that they were added after the machine was first exhibited.

The joy of this project and collaborating with colleagues from a diverse range of academic disciplines is that not only have many questions about the machine’s design and construction been answered, but that this has led to new questions and avenues of research. We have a more comprehensive understanding of John Clark and his Eureka machine now, and it has been preserved for future study and enjoyment.